How Did Dolores Huerta Change The World

How Dolores Huerta Battled Racism And Sexism To Become A Latina Civil Rights Icon

Ever since the 1950s, Dolores Huerta has fought tirelessly to amend the lives of immigrants, women, and the working poor — despite well-nigh being killed in the process.

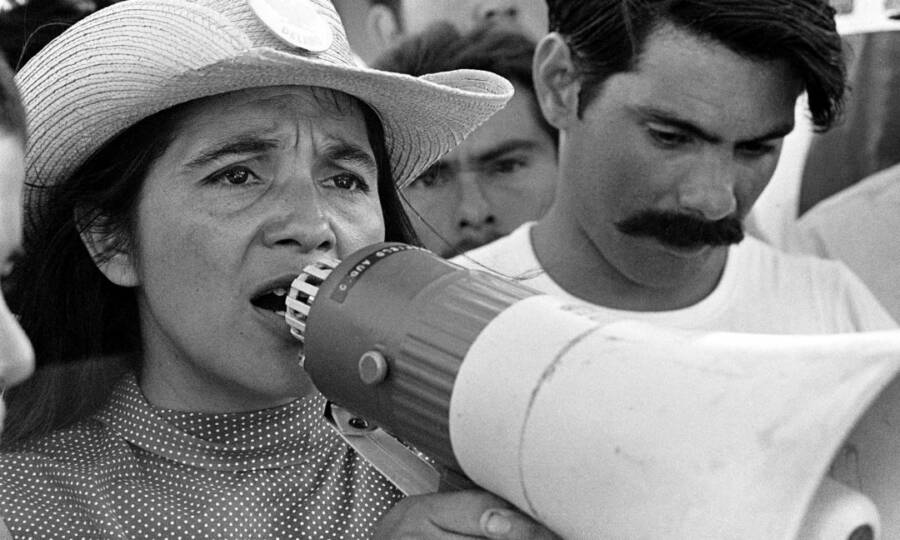

Dolores Huerta Foundation/George Ballis/Take Stock/The Image Works Dolores Huerta rallies farmworkers during a strike in 1969.

Faced with laws that made words like "strike" and "cold-shoulder" illegal, many Latinos in Arizona hesitated to support the growing labor rights movement in the 1970s. Just Dolores Huerta urged them on with a elementary bulletin — "Sí, se puede!" which translates to "Yes, we tin!"

As a young civil rights activist, Huerta faced an uphill boxing to better the lives of Latino Americans. Still, she notched victories like the passage of laws that required driver's licenses and ballots to be offered in Castilian.

Just by the 1960s, Huerta eyed a much larger mission — improving the economic conditions of farmworkers, many of whom were Latino and Filipino migrants. Eager to aid them, Huerta co-founded what would go the United Farm Workers union with young man activist César Chávez. Together, they marched, organized strikes, and demanded better laws.

Hither's how Dolores Huerta'south fearless activism changed the world.

How Dolores Huerta Became An Activist

Dolores Clara Fernández Huerta didn't initially set out to become an activist. Born on April ten, 1930, in Dawson, New Mexico, Huerta spent her early years dreaming of becoming a flamenco dancer someday.

But the desire to help others ran in her family. Huerta's father, Juan, who started out as a farmworker and a coal miner, went on to become a matrimony activist and even won a seat in the New Mexico land legislature. Though Huerta's parents divorced early on, she kept in touch with her father and was impressed by how he used his position to assist people in need.

Meanwhile, her mother, Alicia, operated a hotel that largely served farmworkers in Stockton, California. There, Dolores Huerta watched every bit her mother took intendance of her farmworker clients. When they couldn't pay, Alicia either didn't charge them rent or she let them pay with fruits and vegetables.

"My mother e'er said that you had to aid people that were in need," Huerta said. "That you should not await for anyone to ask y'all to assist them."

Early on, Huerta also experienced discrimination firsthand. In school, a teacher in one case accused her of adulterous on her papers because they were "too well-written." And Huerta was horrified when white men beat out upwards her blood brother for wearing a Zoot-Suit, a style favored by Latino men at the fourth dimension.

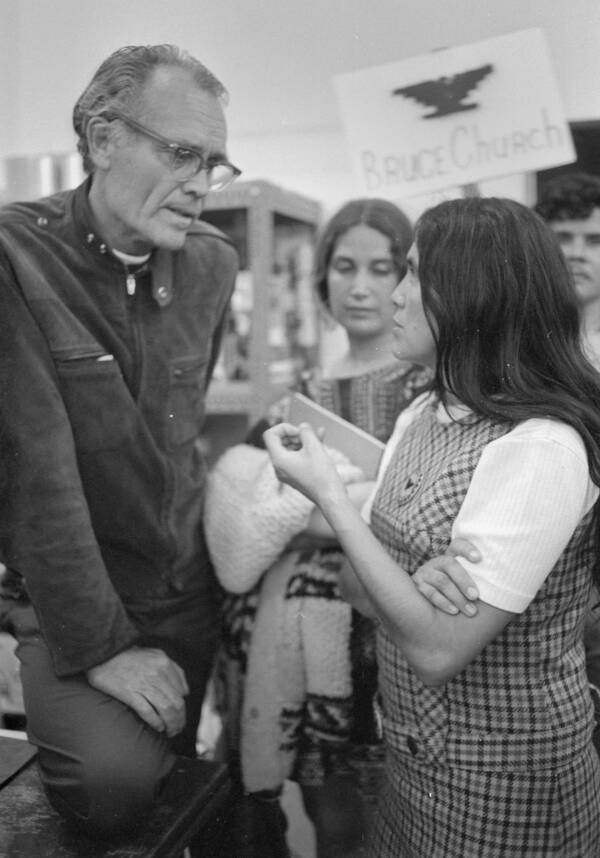

Bob Fitch/Special Collections and University Archives/Stanford University Dolores Huerta, pictured with fellow activist Fred Ross.

But until the 1950s, Huerta lived a rather ordinary life. She got married, had children, got divorced, and pursued a career as an educator. But and then, she began teaching the children of farmworkers: "I couldn't tolerate seeing kids come to form hungry and needing shoes. I thought I could practice more past organizing farmworkers than by trying to teach their hungry children."

Everything inverse in 1955 when she met activist Fred Ross. Years earlier, Ross had helped co-establish the Community Service Organisation (CSO), which focused on fighting for Mexican American rights.

Entranced, Huerta listened as Ross described how the CSO had organized activists, helped register voters alee of elections, and pushed for consequences for constabulary brutality. "That coming together changed my unabridged life," Huerta recalled. "I just felt like I had found a pot of gold!"

With Ross'south encouragement, Dolores Huerta helped found the Stockton chapter of CSO. Tough, tireless, and persuasive, she succeeded in passing 15 bills aimed at improving the lives of Latinos in California.

"We were able to become driver's licenses and ballots in Spanish," Huerta remembered. "Nosotros were able to pass a law that if you lot were a legal resident with a light-green menu, yous qualified for public assistance. [And] we passed [a] voting police force that is still in effect today."

But Huerta wanted to do more. She next turned her formidable gaze to the downtrodden farmworkers of California.

Inside The 1965 Delano Grape Strike

Walter P. Reuther Library/Wayne State University Dolores Huerta with César Chávez (on the far correct) in 1962.

In 1958, Dolores Huerta and the CSO started working with farmworkers, many of whom were poor. "Their furniture was orange crates and apple boxes," Huerta recalled. "And you know that these people were working very, very hard simply they were earning such a niggling scrap amount of money."

Huerta's piece of work brought her into contact with a young activist named César Chávez. Like Huerta, Chávez wanted to do more to help the farmworkers. "We have to start the union," Chávez told Huerta in the early 1960s. "Farmworkers will never have a marriage unless you and I do it."

So Dolores Huerta and César Chávez created the National Farm Workers Association, which after became the United Farm Workers matrimony. Setting their sights on improving the lives of farmworkers in California, they moved near the Delano grape farms and began organizing workers there.

They weren't quite prepared to launch a strike. Simply when Filipino American grape workers in Delano started their own in 1965, Huerta and Chávez decided to help. The strike was different anything they had washed before.

"It was like a state of war," Huerta said. "We never slept. We'd get up at 3 or 4 a.thou. and so nosotros'd go till xi p.m."

She and Chávez helped pb the push to improve conditions for the grape workers. They formed scout lines, organized boycotts, and rallied the strikers. It was dangerous work. Furious growers threatened the strikers with rifles, tried to run them downward with cars, and even sprayed them with sulfur.

The Phillip & Sala Burton Center for Man Rights/Farmworker Movement Documentation Project Dolores Huerta works the sentry line in Delano, California. 1966.

Huerta as well faced sexist vitriol from both her adversaries and her allies. Growers chosen her the "dragon lady." The press ofttimes dismissed her as Chávez's "secretarial assistant" or even his "girlfriend." And men within the movement made so many sexist comments that Huerta started keeping a tape.

"At the end of the coming together, I'd say, 'During the grade of this meeting you men have made fifty sexist remarks,'" she recalled in the book Dolores Huerta Stands Strong: The Woman who Demanded Justice. "Pretty presently I got them downward to 25, then 10, and then 5."

And slowly, the Delano Grape Strike began to gain steam. Members of the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union refused to aid send boycotted grapes. And the United Motorcar Workers started donating thousands of dollars per calendar month to back up the strikers and their crusade. At the height of the strike, 17 million people stopped ownership grapes.

Huerta and Chávez's work also drew the praise of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy. And since Kennedy supported the strikers, they supported his 1968 presidential bid. In fact, Huerta was by his side as he celebrated his California primary win — mere moments before he was assassinated on June 5, 1968. She later mourned his death as the "death of our futurity."

After five grueling years, Huerta, Chávez, and the strikers finally broke through in 1970. The Delano growers agreed to enhance wages to $i.80 an hour (and 20 cents for each box picked). They besides agreed to contribute to the wedlock health plan, and protect workers confronting pesticides in the fields.

Dolores Huerta took the victory. But her battles were far from over.

The Indelible Legacy Of Dolores Huerta

Dolores Huerta didn't rest on her award following the success of the Delano Grape Strike. For the next five decades, she kept up the fight for civil rights in America — even if it meant risking her life in the procedure.

Huerta was arrested more than than 20 times for her function as an activist. And at one point in 1988, she was beaten so brutally past a billy-wielding police officer that her spleen was damaged beyond repair.

She recalled, "I was browbeaten… nigh to the point of decease. They fractured 4 ribs and I had my spleen — well, they never found information technology. The guy hit me then difficult information technology merely burst." Simply despite terrifying incidents similar these, Huerta remained committed to non-violence — in the spirit of Martin Luther King Jr. — and to fighting for the causes closest to her heart.

Equally the vice president of the United Farm Workers — a position she held until 1999 — Huerta continued to support farmworkers. She pushed for amnesty for Mexican laborers, launched new boycotts, and helped improve Latino representation in politics. Her efforts led to the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975 and the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986.

Huerta also turned her attending toward women's rights. In the 1990s and 2000s, she pushed to elect more than women to college political office throughout America. She said, "We need a feminist to exist at the table when decisions are being fabricated then that the correct decisions will be fabricated."

Today, in her 90s, Huerta hasn't slowed downwards. "My personal energy just comes from the work that we have to exercise," she said. "At that place's and then much work out in that location." Her foundation, the Dolores Huerta Foundation, supports communities in their fight for social justice and ceremonious rights.

Wikimedia Commons Dolores Huerta, pictured at a protest in 2022.

Merely despite her impressive career as an activist, Dolores Huerta rarely appears in history books — sometimes on purpose. In 2022, the Texas State Lath of Education voted to remove her from third-form standards because of her amalgamation with the Autonomous Socialists of America.

Meanwhile, some other organizations have been hesitant to embrace her due to her "unconventional" background as a twice-divorced single mother of 11 children. Merely as time has gone on, she's been honored and recognized more and more often for the piece of work that she'southward done.

In 1993, Huerta became the first Latina woman to be inducted into the Women'southward Hall of Fame. And in 1998, she received the Eleanor Roosevelt Human Rights Award. Perhaps most notably, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2022 past former President Obama.

It was and then when Obama acknowledged that Huerta was the inspiration behind his ain famous slogan that he used during his 2008 presidential campaign. As Huerta recalled, "When I met President Obama, the first thing he said was, 'I stole your slogan.' And I said to him, 'Yep, you did.'"

Huerta has expressed gratitude for accolades and honors every bit they come up. But of everything in her long career as an activist and organizer, Dolores Huerta is nigh proud of how she improved the lives of farmworkers.

"They always come to me and say, 'Thanks, cheers,'" Huerta said. "Then I retrieve when I wait dorsum, I think that's one of the important things: bringing humanity to people. When you know that people are actually benefiting from the work that you do, it's very important."

After reading about the inspiring life of Dolores Huerta, discover the story of civil rights activist and congressman John Lewis. So, learn about Emily Davidson, the women'due south rights leader who was run over by a horse.

Source: https://allthatsinteresting.com/dolores-huerta

Posted by: lippertagetaing.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Did Dolores Huerta Change The World"

Post a Comment